Fires impact humans and climate in return. For people, beyond the immediate loss of life and property, smoke is a serious health hazard when small soot particles enter the lungs, Long-term exposure has been linked to higher rates of respiratory and heart problems. Smoke plumes can travel for thousands of miles affecting air quality for people far downwind of the original fire. Fires also pose a threat to local water quality, and the loss of vegetation can lead to erosion and mudslides afterward, which have been particularly bad in California, Randerson said.

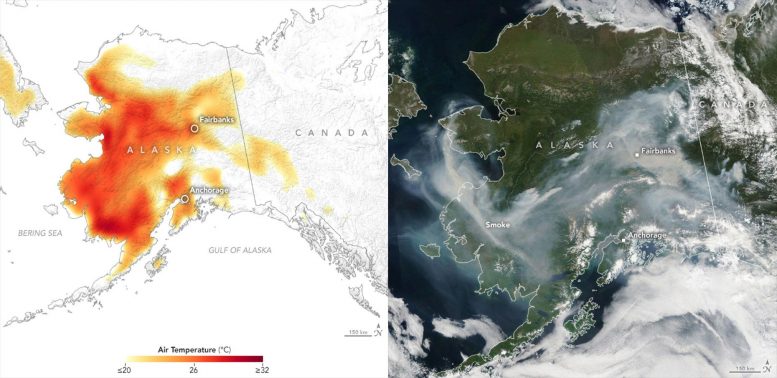

In June and early July 2019, a heatwave in Alaska broke temperature records, as seen in this July 8 air temperature map (left). The corresponding image from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on Aqua on the right shows smoke from lightening-triggered wildfires. Credit: NASA Earth Observatory

For the climate, fires can, directly and indirectly, increase carbon emissions to the atmosphere. While they burn, fires release carbon stored in trees or in the soil. In some places like California or Alaska, additional carbon may be released as the dead trees decompose, a process that may take decades because dead trees will stand like ghosts in the forest, decaying slowly, said Morton. In addition to releasing carbon as they decompose, the dead trees no longer act as a carbon sink by pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. In some areas like Indonesia, Randerson and his colleagues have found that the radiocarbon age of carbon emissions from peat fires is about 800 years, which is then added to the greenhouse gases in that atmosphere that drive global warming. In Arctic and boreal forest ecosystems, fires burn organic carbon stored in the soils and hasten the melting of permafrost, which release methane, another greenhouse gas, when thawed.

Another area of active research is the mixed effect of particulates, or aerosols, in the atmosphere in regional climates due to fires, Randerson said. Aerosols can be dark like soot, often called black carbon, absorbing heat from sunlight while in the air, and when landing and darkening snow on the ground, accelerating its melt, which affects both local temperatures — raising them since snow reflects sunlight away — and the water cycle. But other aerosol particles can be light colored, reflecting sunlight and potentially having a cooling effect while they remain in the atmosphere. Whether dark or light, according to Randerson, aerosols from fires may also have an effect on clouds that make it harder for water droplets to form in the tropics, and thus reduce rainfall — and increase drying.

Fires of all types reshape the landscape and the atmosphere in ways that can resonate for decades. Understanding both their immediate and long-term effects requires long-term global data sets that follow fires from their detection to mapping the scale of their burned area, to tracing smoke through the atmosphere and monitoring changes to rainfall patterns.

“As climate warms, we have an increasing frequency of extreme events. It’s critical to monitor and understand extreme fires using satellite data so that we have the tools to successfully manage them in a warmer world,” Randerson said.

Commentaires

Enregistrer un commentaire